The Obstruction of Justice Provision in the Mar-a-Lago Search Warrant

- On September 23, 2022

- Compliance, Investigations, Litigation, Pearlman, White Collar

The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) raid on President Trump’s Mar-a-Lago resort last month was conducted under a warrant that found probable cause that “evidence of obstruction” would be discovered at the former president’s winter residence. There are several federal obstruction of justice statutes on the books, but the one cited in the warrant was 18 U.S.C. §1519 – a law passed as part of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 in response to the wave of corporate scandals that came to light with the collapse of the energy, commodities, and services company Enron Corporation.

Along with increasing penalties for existing crimes and generally tightening controls on recordkeeping and accounting practices, Congress included §1519 to criminalize anticipatory obstruction, best illustrated by the mass shredding of Enron-related documents done at Enron’s auditing firm Arthur Andersen LLP before the company could be hit with a Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) subpoena.

Arthur Andersen itself was among those prosecuted as a result of its executives, after consulting in-house counsel, repeatedly pressuring its Enron team to “comply with [its] document retention policy.” That edict was widely understood to be a euphemism for destroying Enron-related documents.

In reversing and remanding Arthur Andersen’s conviction, the Supreme Court confirmed that under pre-Sarbanes-Oxley obstruction statutes requiring a “corrupt purpose” as an element of the offense, neither Arthur Anderson nor its officers and counsel could be found guilty of obstruction because it is not “necessarily corrupt for an attorney to persuade a client with intent to cause that client to withhold documents from the Government.” Further, the Court read a requirement into those laws requiring the destruction be linked to a particular government proceeding; even though Arthur Andersen was clearly expecting to be served with subpoenas, that had not yet occurred while the shredding was ongoing.

Congress’ passage of what became §1519 fundamentally changed that landscape. Known as Sarbanes-Oxley’s “anti-shredding provision,” §1519 added a very broadly-worded tool to a prosecutor’s arsenal against those who destroy, alter, or falsify physically documents or electronic records in contemplation of a federal review, audit, or investigation. Unlike its sister statutes that require the government to show that the charged obstructive act had the “natural and probable effect” of obstructing a particular judicial proceeding, §1519 criminalizes “conduct intended to impede any federal investigation or proceeding, including one not even on the verge of commencement.” Yates v. U.S., 574 U.S. 528, 547 (2015).

In its 20 years on the books, §1519 has been used to prosecute a wide array of conduct relating to cover-ups of criminal activity done through destroying, altering, concealing, falsifying, or fabricating evidence of a potential federal crime. This includes the destruction of a passport with a fraudulent U.S. residence stamp and other immigration documents; falsified or exaggerated police reports, and records associated with Medicare or other health care fraud schemes; falsified environmental reports; and falsified records for bankruptcy or business records related to government contracts. The most common cases of electronic data destruction tend to be those involving deleted emails or other documents (including during grand jury investigations), and child pornography. In its early years, it also had been used to prosecute other destruction – such as defendants’ torching of their getaway car after shooting and killing a man on the street. In Yates, however, the Supreme Court struck down its use with respect to property destruction generally; Justice Alito’s concurrence in that case characterizes §1519’s scope as relating to all things “filekeeping.”

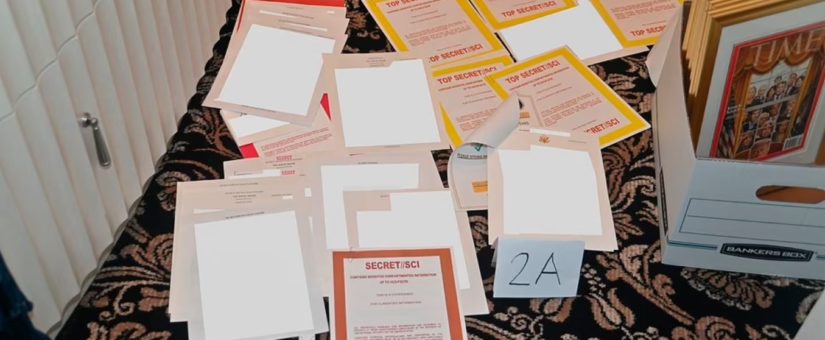

Back to the present case: it seems clear the FBI indeed found at Mar-a-Lago what appear to be documents, including classified ones, that were removed from the White House and are property of the federal government, in addition to the 15 boxes of documents returned to the National Archives from Mar-a-Lago in January. This, notwithstanding a certification by the former president’s attorney to the FBI on June 3 that all responsive documents had been returned following “a diligent search.” Further, the unsealed inventory of items seized in the raid also notes empty folders that once likely contained classified information. On the face of the matter, this suggests a) there may have been material misrepresentations made related to the boxes of documents previously returned, and b) some additional documents not previously returned may have since gone missing or have been destroyed.

Unless certain documents’ classification markings were intentionally and improperly altered, §1519’s applicability to this scenario is agnostic as to whether any of the documents at-issue are actually classified. Nevertheless, the implication of the obstruction charge in this context indicates the alleged conduct extends beyond the possible misappropriation of federal records. If proven, the obstruction charge could imply a deliberate effort to subvert investigators and national security agencies far beyond the acceptable tenets of defending oneself – or one’s client – of suspicions that arise during the course of an investigation.

Though the Mar-a-Lago search brings §1519 prominently into public discussion, the law has been on the books for 20 years. How it will come into play in relation to the former president is yet to be seen, but the episode serves as a good reminder of how this statute can be applied. Companies are still able to enforce regular internal compliance with their legitimate document retention policies, which can and should include regularized document destruction practices. But they cannot, as Arthur Andersen did, use references to document retention as a euphemism or dog whistle to rush to the shredders.

It is a good practice to consult counsel prior to adopting a document retention policy. Lexpat’s team include former federal prosecutors and other experts in scoping and implementing management policies in compliance with federal statutes and regulations. You can email [email protected] to connect with a team member, but remember that communications that occur outside of a formal engagement are not privileged.

A version of this post also appeared on The SCIF, the blog of the National Security Institute at George Mason University’s Antonin Scalia Law School, where Mr. Pearlman is a Visiting Fellow.